Assessing the Impact of the Paycheck Protection Program on the Freight Market

Freight Research • Published on September 28, 2020

As the U.S. economy came to a sudden stop in March, lawmakers enacted the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP), providing emergency loans to help businesses survive the mandatory closures and stay-at-home orders issued in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Despite some hiccups, the program was a success by many accounts. It helped businesses across the country continue to pay employees and avoid bankruptcy. But for the trucking industry, there were also unexpected consequences.

PPP loans allowed carriers to bid below their peers…

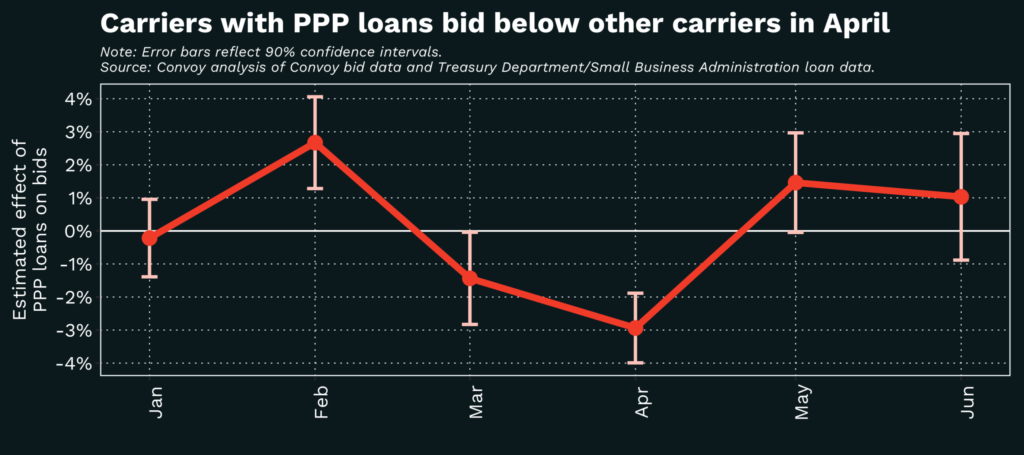

Analyzing the bidding behavior of carriers that did and did not receive PPP loans on shipments available through Convoy’s platform during the first half of 2020, we come to several conclusions.

- We estimate that in April 2020 — after PPP loan distribution began — carriers that received PPP loans initially bid 2.6% below carriers that did not receive loans, and submitted final bids 2.2% below carriers that did not receive the federal loans. (Both results show statistical significance at the 95% confidence level or higher.)

- This behavior was a deviation from the trend that prevailed before the crisis: In January and February 2020, carriers that would later receive PPP loans tended to bid on par with or slightly above other carriers.

- It was also relatively short-lived. By mid-May, the effect had disappeared.

…But participation skewed toward larger carriers

Rules and administrative processes associated with obtaining PPP loans skewed participation in the program toward mid-sized and larger trucking companies, and differences in the sizes of carriers that did versus did not receive PPP loans accounts for some — though not all — of the difference in bidding.

- The median carrier that received a PPP loan in our data had 28 trucks while the median carrier overall has one truck. Excluding the long-tail of owner-operators and very small carriers (fewer than five trucks) from the analysis still yields directionally consistent (though somewhat attenuated) results — with carriers that received PPP loans initially bidding 1.8% below carriers that did not.

Several features of the program made it particularly difficult for smaller carriers to access the program according to carriers in Convoy’s network.

- The program initially required that at least 75% of the loan be used for payroll expenses, which are generally a small fraction of the total outlays for smaller trucking companies that spend more on fuel and vehicle financing/maintenance. It was later relaxed to 60%.

- Loans were originated only by SBA approved lenders. Smaller trucking companies are less likely to have an existing relationship with a business lender, much less a SBA approved lender.

- Strong initial demand for loans meant that the first businesses to apply — which often meant larger businesses that had dedicated finance teams — were more likely to get loans from the initial round of funding than smaller businesses.

For the trucking industry, the fact that participation in the program skewed toward mid-sized and larger carriers means that the trucking industry that emerges from the crisis will likely be composed of somewhat fewer, larger trucking companies — a shift that was already in progress pre-crisis, but that was likely accelerated by the PPP loan program.

The program helped some carriers avoid bankruptcy

These results beg the question: Would the freight industry — and carriers in particular — have been better off without the PPP loan program? A complete accounting of the program’s effects would tally both the number of carriers that were saved from bankruptcy and weigh it against the number of carriers that were pushed to the brink as a result of lower rates, as well as their foregone revenue.

There is some evidence that the program did contribute to fewer carrier bankruptcies — at least in the near term.

The bankruptcy rate among federally registered truckload carriers had been gradually increasing leading into the crisis. But in late April and early May — just as PPP funds were hitting bank accounts — it halved, before resuming its pre-crisis trajectory in June. Among mid-sized and large carriers that bid on Convoy loads during the first five months of 2020 and that did not receive any PPP funds, a small number had gone bankrupt by June; among their peers that did receive PPP funds, none had gone bankrupt.

There are plausible alternative explanations for the dip in carrier bankruptcies observed in late April and early May. The sudden surge in freight demand in March temporarily pushed up freight market rates, perhaps allowing some carriers to forestall bankruptcy the following month. Administrative delays in bankruptcy filings during the most restrictive phase of the shutdowns might have artificially deflated the April numbers. But the accumulating evidence increasingly points toward the same conclusion.

Main takeaway: It’s complicated

With the PPP loan program only a few months in the rear-view mirror, its consequences for the trucking industry are perhaps best summarized as “complicated” — for two primary reasons.

- First, available evidence suggests that it likely prevented some bankruptcies but also pushed market prices for trucking services modestly lower.

- Second, the program’s design made it less accessible to the trucking industry than it was to other sectors of the economy, and within the trucking industry, it was more accessible to mid-sized and larger carriers than to small carriers and owner-operators.

As is often the case when assessing the real-world consequences of economic policy decisions, there is no single piece of conclusive evidence and it is too soon to write a definitive history. But there is a lot of data all pointing in the same direction.

Methodology

In July 2020, the Treasury Department and Small Business Administration (SBA) published data on PPP loan recipients. We combined this public data set with Convoy’s data on carriers’ bidding behavior for specific loads on the freight market.

We cleaned the Treasury/SBA data using conventional text and address parsing techniques to ensure as high a match rate as possible with Convoy’s internal data, and then matched the two data sets on business name, business address, and business ZIP code. It’s possible that, despite our precautions and data cleaning, some potential matches were dropped due to inconsistent business names or addresses across the two data sets.

The Treasury Department and SBA published partial data (excluding the recipient’s name and address) for recipients of loans less than $150,000, so our analysis is only based on recipients of larger loans. That means that the reference group of recipients who we classify as having not received loans includes some carriers who actually did receive small loans, potentially biasing our estimate of the magnitude of the effect of the treatment (i.e., receiving a loan) toward zero, yielding an overall conservative estimate of the program’s effect.

For the analysis presented above, we included only loads that received at least one bid from a carrier that is identified as having received a PPP loan, and at least one bid from a carrier that did not receive a PPP loan. The analysis covers over 42,000 open market bids by nearly 9,000 carriers during the first half of 2020. The combined data set with these additional restrictions is not necessarily reflective of the universe of shipments available or completed through Convoy’s platform.

View our economic commentary disclaimer here.