Where did all the drivers go?

Carriers, Freight Research, Shippers • Published on May 7, 2021

With sky-high expectations for surging job gains as the reopening of the economy accelerated, the April Jobs Report had every reason to disappoint. Employment growth was strong compared to a “normal” month over the past decade but underwhelming compared to job gains in recent months; stable unemployment, shadow unemployment and labor force participation are also not what economists expected. In the transportation industry, trucking firms shed 1,500 jobs and courier/parcel delivery firms shed 77,400 (both seasonally adjusted) — an unusually large decline for April, suggesting that some last-mile delivery workers may have been kept on payrolls longer after the end-of-year holiday rush longer than they have been in the past.

Still, the American labor market has made a remarkable recovery a year after the U.S. economy shut down during the early weeks of the Covid-19 pandemic, pushing 17 million workers into sudden unemployment and throwing the trucking economy into a brief freefall. April jobs market data released this morning by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) would have been unimaginable just a few months ago.

During the dark days of Spring 2020, few would have anticipated that just 12 months later firms would be struggling to find enough workers. But that is indeed happening: More than a third of companies surveyed by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York in April 2021 cited labor availability as a “major constraint” to growing their businesses and the National Federation of Independent Business’ index of businesses unable to find skilled workers hit an all-time high going back to the 1970s. Casual talk of labor shortages is inherently controversial: Those looking to hire tend to see shortages around every corner while existing workers will often point to more generous compensation as the most obvious market clearing mechanism.

Rising prices signal some degree of — perhaps temporary, perhaps more enduring — supply/demand imbalance in the freight market. The fact that trucking industry employment reported today by the BLS was still 3% below where it was on the eve of the pandemic in January 2020 adds further fuel to the idea that something isn’t working in the labor market for truckers. (As we’ve previously noted, the employment numbers reported in BLS’ monthly jobs report don’t cover the full universe of truck drivers.) It’s worth asking: Where did all the drivers go?

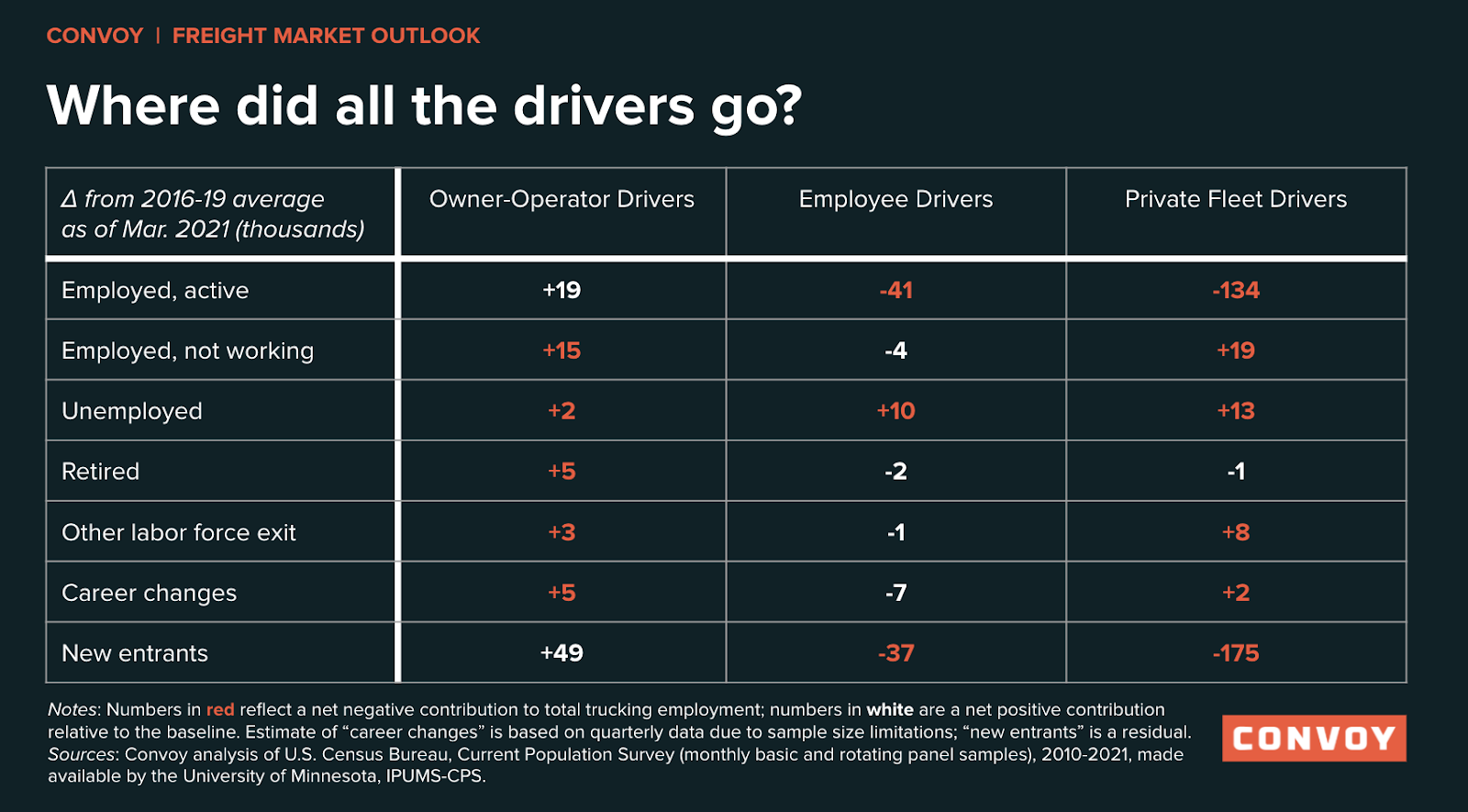

Household survey data through March suggest that there is no one-size-fits-all explanation for the trucking industry’s labor woes. (The survey data is available only through March since publication of the detailed results lags the BLS report by several weeks.)

- Shadow supply of owner-operators is elevated, but new entrants have offset exits. Active employment among owner-operators is at or above pre-pandemic levels (depending on the benchmark one references), but there is also evidence of elevated numbers of owner-operators sitting on the sidelines of the labor market (e.g., employed but not working, unemployed, or having recently left the labor market for retirement or other reasons). The gap between elevated slack and net employment gains for owner-operators has been driven by reasonably strong new entrants.

- New driver recruitment, not workers on the sidelines of the market, is the primary challenge for fleets. The situation is very different for company drivers: Employment is below pre-pandemic levels according to various benchmarks, and there is no evidence of elevated numbers of company drivers on the sidelines of the labor market. If anything, indicators of shadow supply are below pre-pandemic levels for company drivers. This suggests that the main challenge for fleets is recruitment and retention: New driver inflows are well below historic norms. Since fleet employment outnumbers owner-operator employment by several orders of magnitude, their inability to attract new drivers has contributed to a net decline in the number of active for-hire drivers.

The slow and inelastic response of labor supply to trucking demand is the industry’s headline preoccupation. There have been other smaller, easily overlooked, shifts in the backdrop.

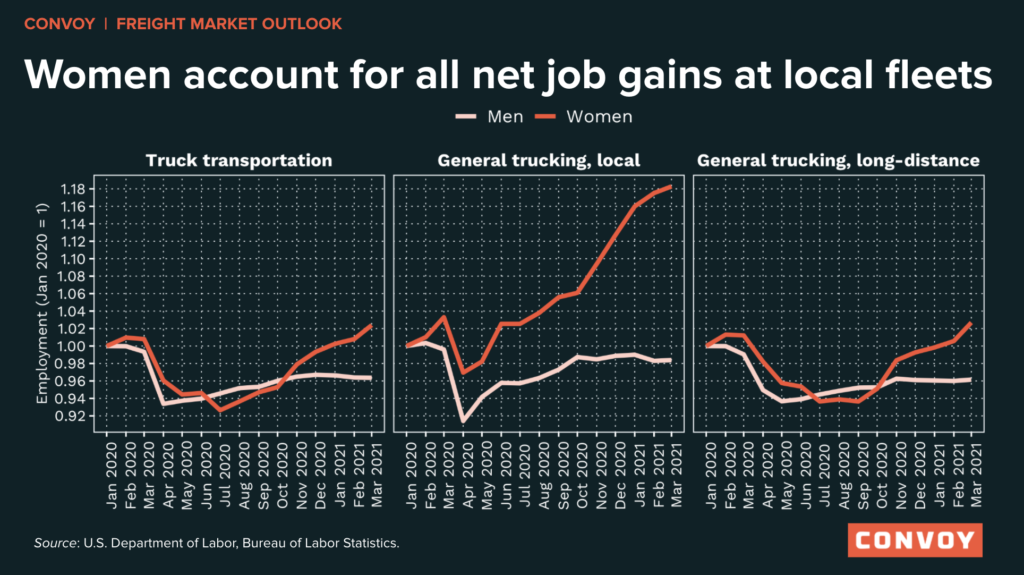

BLS data disaggregated by gender show that women are still a tiny fraction of trucking industry employment, but they have made substantial progress over the past year, particularly at companies that focus on local/regional hauls. As of March, the number of women employed at truck transportation companies is 2.3 percent above where it was before the pandemic, while among men, employment is still 4 percent below where it was. At firms that focus on local/regional hauls, employment among women is 18 percent above pre-pandemic levels — which works out to about 5,000 additional employees — while among men it’s 2 percent below, a net decline of about 5,000 employees. Employment of women at long-haul fleets is also above pre-pandemic levels, but by a much smaller margin. (Publication of employment data by gender lags the official Employment Situation Report by several weeks, so the March 2021 data is the most recent.)

Over-the-road lifestyle considerations have long been identified as a barrier to women in trucking, but the industry is slowly and gradually shifting toward more and more reliance on shorter local and regional hauls as supply chains and distribution networks adapt to more active inventory management. This should make trucking more attractive to all workers who have a preference for staying closer to home. It will also amplify the impact of efficiency gains, since the most practical productivity enhancements focus on helping truckers make the most of their regulation-constrained hours.

View our economic commentary disclaimer here.