Why We’re Launching Freight Economics Research on the Convoy Blog

Freight Research • Published on June 13, 2019

Today we are launching Freight Economics at Convoy — an initiative to feature the best of our economic analysis and freight data on the Convoy Blog and to share our perspective on freight market developments.

As a marketplace that connects shippers that move goods around the country with the tens of thousands of carriers who move those goods, Convoy relies on an objective assessment of market conditions, guided by industry-leading data science. This data provides a detailed look into the current and future states of both our industry and the industries that we serve. Our Economic Research team, which is part of our rapidly-growing Data Science team at Convoy, closely tracks and helps forecast these developments.

But this initiative aims for more than just that.

From the food we eat to the goods we buy and sell, freight data provides an unconventional window into the broader American economy well beyond the nation’s highways and truck stops.

Trucking is one of the most common jobs in the country, if not the most common job [1]. National freight metrics have historically tracked pillars of the overall economy — such as manufacturing, agriculture, and trade. Nearly every consumer product — and often the inputs used to make those products — has touched the nation’s freight network at some point (often multiple times). The inefficiencies that exist today in the freight industry are a hidden part of the price all consumers pay.

Trucking is also at the intersection of some of the thornier challenges facing the American economy, as we describe in greater depth below.

The shifting American labor market

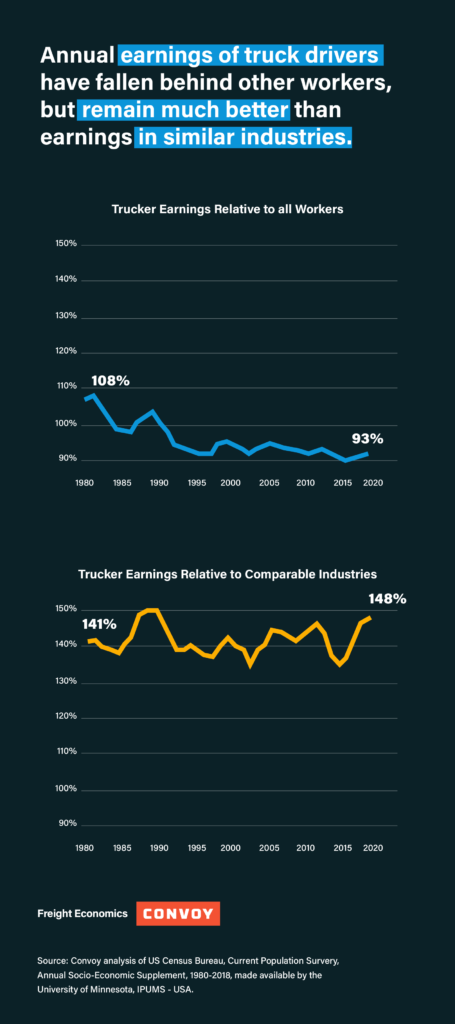

Unlike managerial jobs, truck driving is largely comprised of Americans with comparatively fewer years of formal education. In the early 1980s, the median truck driver earned slightly more than the typical worker nationwide. Since then, truckers have lost ground compared to the overall labor force (chart 1).

However, compared to other industries that employ workers with a similar demographic profile, truck drivers have consistently commanded a roughly 40-50 percent earnings premium.

While not as well-paid as the much more dangerous and much more volatile jobs in extractive industries (e.g., oil and gas), trucking has offered a path to middle-class stability for workers who have seen diminishing prospects in the broader American labor market over recent decades. This path is increasingly rare in other industries that employ large numbers of workers with little formal education, such as food service and agriculture. (Construction is perhaps the closest competitor though at the median, construction workers earn 4% — about $1 per hour — less than truckers.[2])

Small businesses in a big industry

The trucking industry depends on a diffused network of owner-operators — essentially self-employed entrepreneurs who both own their truck (possibly a couple of trucks) and drive them. About one-in-ten private-sector truck drivers is self-employed. [3]

Entrepreneurship and small business hold a mythical place in the American popular imagination, but the share of Americans who are self-employed has dwindled since the 1980s, in part because of increasing specialization and complexity in many industries. [4] In part, this has also happened because, for many jobs, there simply do not appear to be rewards to self-employment.

Other occupations that have historically been dominated by small businesses — including jobs like doctors, lawyers, construction workers and real estate agents — have seen much sharper declines in the self-employed segment. There is no single reason why small businesses and the self-employed have struggled in recent decades. While not fully immune from these challenges, the trucking industry is a powerful counterexample of how small businesses and entrepreneurs can succeed.

Macroeconomic ebbs and flows

While the rest of the economy was accelerating over the past 12 months, most freight metrics slowed sharply, raising questions as to whether freight’s troubles were a canary in the coal mine — a leading indicator of broader troubles ahead — or an idiosyncratic footnote in an otherwise booming American economy.

To be sure, freight metrics have historically led the national business cycle. But beyond freight, economic data have proven remarkably resilient through the first five months of this year. And the recent slowdown in freight comes in the wake of a rapid run-up in prices. Since last year’s surge in freight prices, supply has increased as carriers invested in new trucks, anticipating continued price gains. So to some degree, the decline has been less of a collapse and more of a normalization as the market finds a new balance.

But with prices dropping sharply late last year and early this year, freight markets are again searching for balance: The pendulum swings sharply toward one extreme only to reverse course. Some of last year’s truck orders are being canceled and some drivers are being temporarily lured into more lucrative lines of work — particularly as construction labor demand heats up. An expected easing, due this summer, of regulatory restrictions on the number of hours drivers can be on the road will dampen the usual supply response to low prices: those drivers who do remain on the road will be able to increase their hours to make up for lower rates.

Stepping back from the noise of incoming data, we tend to view the economy in opposing states of recession or expansion that have a similar timing and effect across the country. Reality is more complicated.

Unlike economists’ charts, there are no bright lines in time or shaded bars in the soil dividing booms from busts. Instead, economic activity ebbs and flows. There are periods of slowing — if not outright contracting — economic activity short of recessions. The country’s diverse communities and industrial sectors do not experience the same timing or magnitude of expansions and contractions. Freight data have the potential to shed light on these unique regional dynamics.

The road ahead

For these, among many other reasons, we are excited about this effort and the opportunity to bring new data and new analytic tools to an industry that touches every corner of American life. It is a sector that has, in recent years, largely been overlooked in attempts to understand our country and economy. At Convoy, we hope to begin to fill that gap in the months and years ahead.

As we ramp up to full speed, we’ll post periodic updates here on Convoy’s blog.

View our economic commentary disclaimer here.

[1] Second only to generic “managers” if they are all counted as a single category. Convoy analysis of U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey (CPS) March Supplement 2000-2018 made available by the University of Minnesota, IPUMS-USA.

[2] Convoy analysis of U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey (ACS), 2015-17 made available by the University of Minnesota, IPUMS-USA. Includes employed private-sector workers.

[3] Convoy analysis of U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey (ACS), 2015-17 made available by the University of Minnesota, IPUMS-USA. Includes employed private-sector workers.

[4] This refers to workers whose primary occupation is at a business they own; it does not account for gig-economy workers.